13 December 2022 | Articles, Articles 2023, Communications | By Christophe Lachnitt

China’s “Blank-Page Revolution”: Silence Is Truly Golden

A totalitarian regime caught at its own game.

The current wave of protests against China’s totalitarian regime began after a fire engulfed an apartment building in Urumqi (the capital of Xinjiang, in the northwest of the country) and killed ten people (according to the official data) who were imprisoned in their homes because of the zero Covid policy. Footage showed fire fighter trucks stationed away from the blaze and audio recordings revealed trapped residents screaming before they died. The reaction was overwhelming: Millions of messages flooded the Chinese Internet denouncing the severe restrictions imposed by the zero Covid policy, which citizens believe is responsible for the tragedy.

The protests that followed in Urumqi are all the more extraordinary because this region and this city are probably the most closely watched on the planet due to the genocide that the Chinese communist government is perpetrating there against the Muslim Uyghur people. Those protests spread on social media to the rest of the country (Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, Harbin, Nanjing, Shanghai, Wuhan…) where the rejection of the zero Covid policy was expressed too powerfully for the state censorship to do its job immediately. Students frustrated by months of being blockaded on their campuses organized silent demonstrations and vigils to honor the dead of Urumqi. The symbol of what has come to be known as the “A4 revolution” or “blank-page revolution” soon became the blank sheets of paper waved by protesters, a sublime symbol of the struggle against the totalitarian censorship imposed by Xi Jinping. “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people things they do not want to hear,” George Orwell1 said. When, like Chinese citizens, one is deprived of this freedom, one lets the oppressor read between the lines of one’s silence. There are two opposing silences: The literal one imposed by the tyrant and the symbolic one displayed by resistance fighters. If the latter is imposed by repression, the former is a weapon. This revolutionary silence can be expressed even more creatively as pointed out by these students who show the equation of Friedmann, a mathematician whose name is pronounced almost like “free man.”

Demonstrations in China are less rare than one might think in the West, but what makes them exceptional is the cohesion of the movement and the demands it expresses. As Yasheng Huang, a professor at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and author of the excellent book “Capitalism With Chinese Characteristics”, notes, Xi Jinping has, with his zero-covid policy, “violated a time-tested technique his predecessors used to defuse social tensions: Divide and conquer. After 1989, most of the Chinese protests were localized and issue-specific. Rural residents lost their land, but urbanites were showered with benefits. State workers lost their jobs, but private entrepreneurs were wooed to open businesses. The benefits and losses evened out in the end. Different people harbored different grievances, and their grievances were not synchronized. […] Now consider China’s zero-Covid policy. Its lockdowns put nearly everybody in exactly the same situation, and according to one estimate, almost 400 million people were put under some sort of lockdown in 2022. The affluent Shanghainese have very little in common with people in Urumqi in Xinjiang. Yet when 10 people died in a fire in a high rise in Urumqi, with building doors allegedly locked because of Covid restrictions, empathy, a crucial ingredient in collective actions, arose among Shanghainese who inhabit similar high rises. Never, not even in 1989, had a Chinese regime confronted protests in many cities at the same time.” In reality, with his zero Covid policy, Xi Jinping has broken the implicit social contract between the Communist Party and its citizens: Prosperity in exchange for a deprivation of freedom leaving some space for autonomy.

(CC) Thomas Peter-Reuters

Unsurprisingly, the government blamed foreign action for this wave of protests, which all the evidence suggests is entirely domestic, sparked perhaps as much by the disappearance of Xi Jinping’s term limits from the constitution in March 2018 as by the three years of zero Covid policy. Xi Jinping’s endless reign seems all the longer these days as Jiang Zemin, a leader with whom the Chinese had more affinity than with “Uncle Xi,” has just passed away. It was in Shanghai that, on the evening of Saturday 26 November, around Urumqi Street (quite a symbol), the first demonstrators called on | Xi Jinping to resign. The next day, the movement resumed, and the repression intensified: This video shows, for example, a man brandishing a bouquet of flowers and asking aloud if it is a crime to do so being taken away in a police car, but not without having proclaimed that “We Chinese need to be a little braver!” The brutal intervention of the police put an end to the main demonstrations and hit some Westerners to the despair of Chinese citizens.

It must be said that, after the surprise effect created by this unforeseen indiscipline, the Communist totalitarian state set about taking advantage of its sprawling digital surveillance system, as illustrated by this anecdote reported by The New York Times: “When Mr. Zhang went to protest China’s strict Covid policies in Beijing, he thought he came prepared to go undetected. He wore a balaclava and goggles to cover his face. When it seemed that plainclothes police officers were following him, he ducked into the bushes and changed into a new jacket. He lost his tail. That night, when Mr. Zhang, who is in his 20s, returned home without being arrested, he thought he was in the clear. But the police called the next day. They knew he had been out because they were able to detect that his phone had been in the area of the protests, they told him. Twenty minutes later, even though he had not told them where he lived, three officers knocked at his door.” Mr. Zhang’s misadventure is representative of what so many other peaceful demonstrators have endured as police officers have come into their homes, terrorized them, and searched their smartphones for banned Western applications, as is now also the practice of law enforcement officers on the streets. When it is not the tracking of smartphones that betrays protesters, they are spotted by the millions of cameras installed in cities and facial recognition software that analyzes the videos to identify rebellious citizens. While that digital surveillance system has been used until now mostly against dissidents, ethnic minorities, and foreign workers, this is probably the first time it has been implemented on such a large scale against the Chinese middle class. This digitization of totalitarianism gives a different outcome to this wave of protests than the previous one of the same magnitude that ended in blood on Tiananmen Square in 1989: Close interrogation with police officers and deterrent threats to prevent recurrence discourage most of the protesters.

At the same time, the Communist government has further tightened censorship of the digital space and has made sure to prevent any use of VPNs (virtual private networks) that allow circumvention. Over the last few years, as the Chinese Internet has become more and more regulated, the Chinese have learned to use VPNs to access Western applications in order to be able to collect trustworthy information (especially on Twitter, where the account of a Chinese man based in Italy is among the most followed) and distribute it (especially via Telegram). Apple, which is never stingy with moral baseness to help Chinese totalitarianism, has reduced the usefulness of its AirDrop local file sharing feature for resistance fighters by limiting, only in China, the visibility of iPhones by other people to only ten minutes at a time.

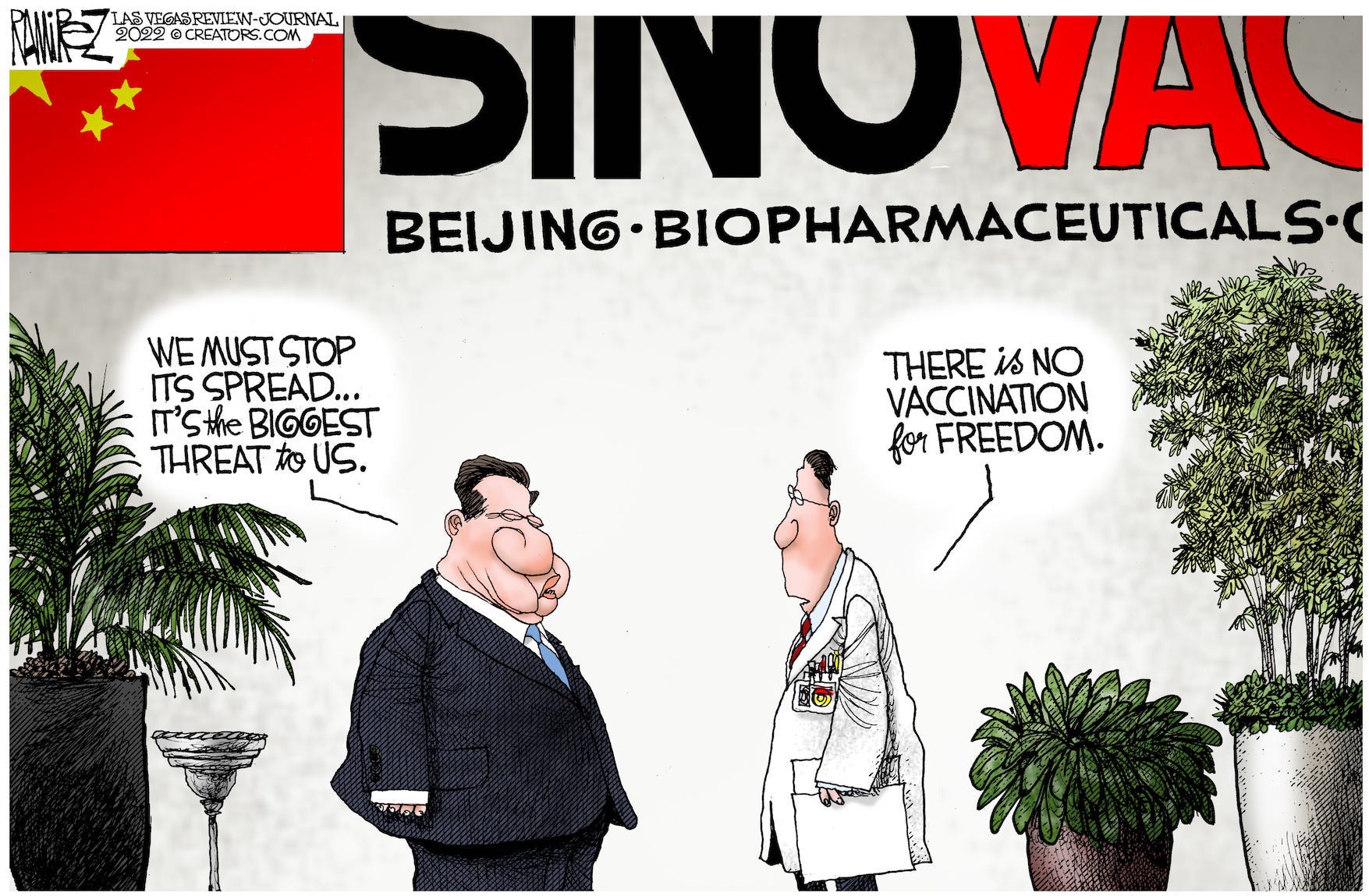

Finally, to complement this all-repressive policy, the government has announced the relaxation of certain constraints stemming from its anti-Covid strategy. Yet, despite – or because of – three years of zero Covid policy, China is ill-prepared to deal with the consequences of a relaxation. According to the government’s own data, investment in medical infrastructure expansion, such as hospital beds, slowed during the pandemic, as financial resources were devoted to testing and quarantines. Incidentally, the same causes have had devastating effects in Hong Kong, which is suffering from one of the highest per capita mortality rates in the world this year. As for the vaccine approach, it represents a clear failure, especially because, for ideological reasons, the Chinese state refuses to use Western vaccines that are more effective than its own products. The result is that a large number of vulnerable citizens, primarily the elderly Chinese, are very poorly protected against the virus. A recent analysis by life science company Airfinity showed that lifting the zero Covid policy could put between 1.3 and 2.1 million people at risk of death.

Another consequence of the zero Covid policy was that the confinement of several hundred million people to their homes or to dedicated centers – probably the largest freedom deprivation initiative in history – meant that the Chinese people watched the World Cup intensely on television, having nothing else to do. They discovered with rage that the rest of the planet, far from being “on the brink of collapse” as Communist propaganda claims, was living normally despite Covid, without even wearing masks in the stadiums of Qatar, a discovery that generated a new form of censorship.

Viktor Frankl, psychiatrist and founder of logotherapy, the theory of the meaning of life, wrote in his masterpiece2 that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: The last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” This is what the Chinese people are confirming by adopting the conduct that the authorities wanted to impose on them: Silence.

The greatest challenge to an oppressor is sometimes to realize his aspiration.

—

1 “The Freedom of the Press,” proposed preface to “Animal Farm.”

2 “Man’s Search for Meaning.”