15 March 2024 | Articles, Articles 2024, Management | By Christophe Lachnitt

In The Age Of Artificial Intelligence, Can Companies Still Succeed Slowly?

Are organizations in danger of speeding up?

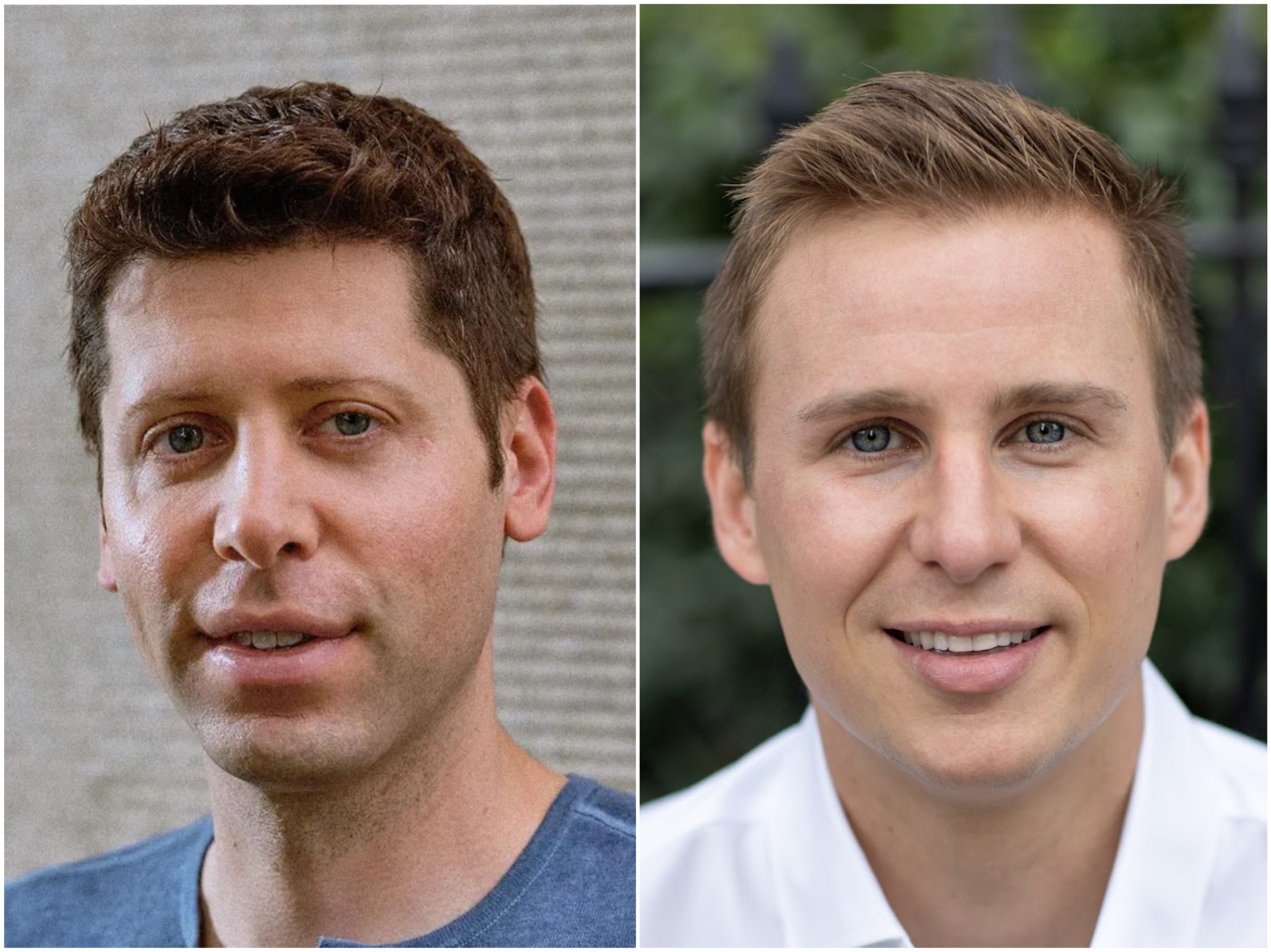

Today, I would like to talk to you about the managerial visions shared by two of the most intriguing and successful entrepreneurs of their generation. One, Sam Altman, has become a household name because the company he co-founded, OpenAI, is at the forefront of the generative artificial intelligence revolution. The other, Brett Adcock, is unknown, although his life story and entrepreneurial record are even more interesting than those of Sam Altman.

Brett Adcock is an entrepreneur I’ve been following for some time now. Born on an Illinois farm into a farming family, he founded his first company, Vettery, at the age of 26. It was an artificial intelligence-powered marketplace designed to match companies with candidates, so that the latter could find the job that suited them best. He developed Vettery until it had several hundred employees and a network of 30,000 companies. In 2018, Vettery, whose artificial intelligence systems were conducting 20,000 interviews a month, was acquired by Adecco for $110 million. Brett Adcock then set himself a new challenge: Designing an electric vertical take-off and landing (eVOTL) aircraft for urban mobility. He founded and self-financed Archer Aviation. Like Elon Musk with SpaceX and Tesla, he spent a year learning the fundamentals of the sector and associated technologies. Brett Adcock returned temporarily to the University of Florida, where he began studying eVOTL engineering while building the Archer team and roadmap. A few years later, he signed a $1.5 billion commercial agreement with United Airlines and took Archer Aviation public at a valuation of $2.7 billion. In 2022, he founded and self-financed Figure, one of the pioneers of humanoid robots – robots that share a number of physical characteristics with human beings so as to be able to take on some of their tasks -, and started the learning process all over again in a new technological field. Figure has just closed a financing round valuing the company at $2.6 billion, and signed a partnership with BMW to help operate its largest industrial site in the USA. As you can see, Brett Adcock is the most underrated entrepreneurial genius of our time.

With introductions out of the way, let’s take a look at the statements by these two executives that caught my attention.

In a blog post dedicated five years ago to the managerial lessons he had learned from his own experience and observation of “thousands of entrepreneurs” (in his role as President of incubator Y Combinator), Sam Altman explains:

“Focus is a force multiplier on work. Almost everyone I’ve ever met would be well-served by spending more time thinking about what to focus on. It is much more important to work on the right thing than it is to work many hours. Most people waste most of their time on stuff that doesn’t matter. Once you have figured out what to do, be unstoppable about getting your small handful of priorities accomplished quickly. I have yet to meet a slow-moving person who is very successful.“

Sam Altman – (CC) Ian C. Bates/The New York Times/Redux and Brett Adcock – (CC) YouTube

For his part, Brett Adcock put it this way in an interview last year:

“At a company, especially early stage, you really have two levers. You have a compass, and you have a speed. So, you really want the compass to be dialed the right way and you really want to hit the gas as hard as you can. You don’t want to hit the gas the wrong way. It’s really tough. Early enough, it’s fine, but when you get bigger, it’s a big ship with a small rudder. It’s really tough to change directions. In both Archer and Figure, I wrote the master plan, which goes online. It’s like a 10-year vision document. We have a culture doc, which I also wrote, defining our culture and what you should expect if you come over here. I think if you come here, one of the big shocks somebody might have from a big corporate somewhere else is that we move incredibly fast and we want to ship product as quick as possible and recursively make it better. I think the rest of the stuff is almost like these guardrails to help that out, like the culture, the master plan, the people. Everything is supporting this river that’s flowing and it’s flowing fast so we can control where it flows to, but we really want to ship product really quick. My advice to a lot of entrepreneurs in the early days, the most important thing we could be doing as an organization is focusing on product and shipping product, not working on PR, not working in some ways on getting the brand perfect or getting the right article in TechCrunch. It’s really about getting the useful product or service out the door.“

The role of speed in a digitally-driven world is nothing new. I remember that, in the 1990-2000s, John Chambers, then head of Cisco (the Nvidia of the time), repeated over and over that, in the corporate world, “It’s no longer the big beating the small, but the fast beating the slow.” Admittedly, it may be possible to identify a few business sectors that are completely sheltered from digital technology, if there are any left, where speed is not a condition for success.

But for the rest, the role of speed in organizational performance will only increase with the advent of generative artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence is an exponential technology, progressing by leaps and bounds rather than in a linear fashion. Any delay in its adoption and development can result in being left behind, magnified a hundredfold, especially as the spread of quantum computing will give it, like many other innovations, an extra boost.

Beyond this technological context, there are two final comments to make about the role of speed. First, we must not confuse agitation with movement, activity with progress. This is one of the reasons why the definition of priorities emphasized by Brett Adcock and Sam Altman is so important. Second, going fast also allows us to fail quickly (“fail fast”, according to one of Silicon Valley’s mantras), while failing constructively because it is deliberately instructive (“fail forward”, its corollary). This is why the right to make mistakes is often consubstantial with success.