9 November 2014 | Articles, Articles 2014, Communications | By Christophe Lachnitt

What Role For Publishers In The New Media Value Chain?

Ben Thompson devoted an article on his blog to the role of publishers in the new media value chain created by the increasing dominance of major digital platforms.

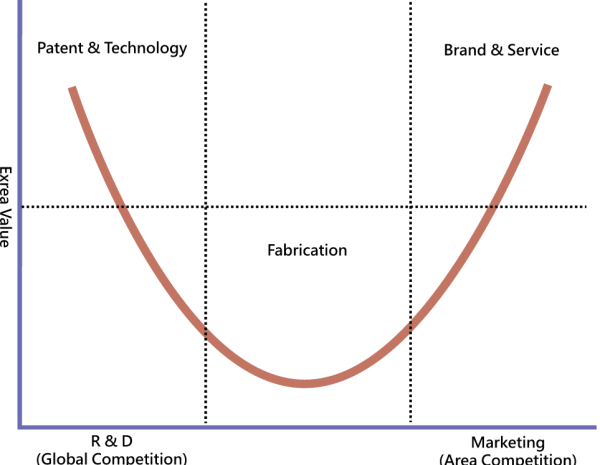

Thompson elaborates on the concept of “smiling curve” created by Stan Stih, founder of Taiwanese computer maker Acer. It is “an illustration of value-adding potentials of different components of the value chain in an IT-related manufacturing industry. (…) Both ends of the value chain command higher values added to the product than the middle part of the value chain.” (see graph below)

(CC) Rico Shen

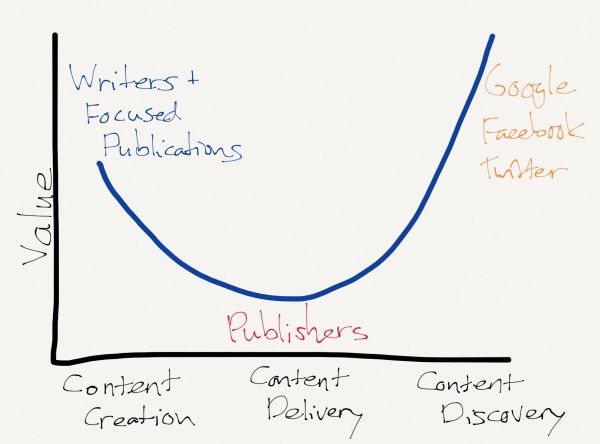

Thompson applies this principle to the media industry. In substance, he writes that publishers are at the center of the media value chain, while major digital services (Facebook, Google, Twitter…) and content creators are on both sides of the chain.

“When people follow a link on Facebook (or Google or Twitter or even in an email), the page view that results is not generated because the viewer has any particular affinity for the publication that is hosting the link, and it is uncertain at best whether or not their affinity will increase once they’ve read the article. If anything, the reader is likely to ascribe any positive feelings to the author, perhaps taking a peek at their archives or Twitter feed.

Over time, as this cycle repeats itself and as people grow increasingly accustomed to getting most of their ‘news’ from Facebook (or Google or Twitter), value moves to the ends. (see graph below)

This trend isn’t limited to publishing, either. Last week HBO announced that it was finally going direct to customers; while I think declarations that this decision will lead to cord-cutting are massively overstated, it is certainly a devaluing of the cable middle person.”

(CC) Ben Thompson

Overall, I can only agree with Ben Thompson’s analysis since it converges with several trends that I have discussed on Superception, first and foremost the evolution of the concept of media, the creation of personal brand journalism businesses, the success of anonymous content producers on sharing platforms, the increasingly tough economic equations facing the written press, the rise of native advertising, and the creation of media entities by brands.

However, I will offer three comments in order to make Thompson’s view less deterministic:

- It seems to me that his analysis works better for general content deliverers than for vertical and community media. The latter generate a much higher audience loyalty and need less assistance from content discoverers to attract their public. One can find an illustration of this phenomenon in the success of vertical publishers as diverse as The Financial Times and Zillow.

- One of the ways for general media to escape the trap described by Ben Thompson is to morph into vertical or community publishers in order to create a stronger connection with their audiences. This is what I would call the Netflix model. Such a community can be created around (i) content original enough to generate audience loyalty, (ii) services attractive enough to become a must-have, and (iii) a value-laden brand powerful enough to create public excitement.

- Taken to its extreme, Ben Thompson’s logic would lead to the gradual disappearance of publishers. As a matter of fact, almost every content creator who has gained a significant audience in the recent past has set up their own publishing entity – mostly vertical or community media – and hired several content creators.