19 September 2019 | Articles, Articles 2019, Management | By Christophe Lachnitt

Is Corporate Purpose A Fad?

181 CEOs, whose companies account for about one-third of the U.S. market capitalization, recently issued a joint statement. They commit to deliver value to all of their stakeholders: Customers, employees, suppliers, communities in which they work, and shareholders.

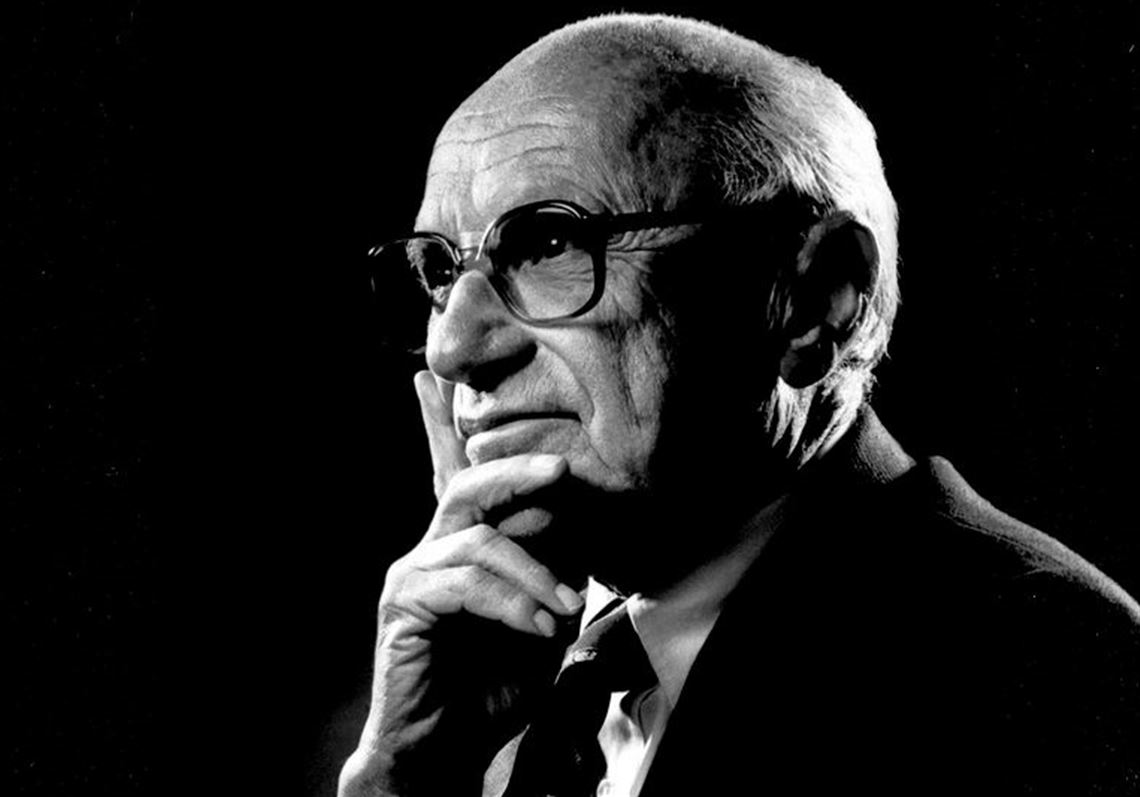

Since 1970, America’s view of corporate value creation has been dominated by Milton Friedman’s model of shareholder capitalism. The Economy Nobel Prize awardee proclaimed that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Even though U.S. entrepreneurs have created some of the world’s most socially responsible companies (Patagonia, Salesforce, Southwest Airlines, Starbucks, Whole Foods Market…), that approach did not prevail until now.

However, a joint study by Ernst & Young and Oxford University shows that the public discourse on corporate purpose has increased five-fold between 1994 and 2016. The problem is that, more often than not, it was much ado about nothing. The more companies communicated about their purpose, the less they seemed to actually implement it.

A corporation should not discover by chance that it has a purpose: Defining a purpose is an introspective work. Except for startups that start from a blank page, a purpose is a collective belief that must result from a sincere process. It cannot be dictated by the CEO, the Executive Committee or the Board; it must involve as many employees as possible.

The pledge signed by 181 CEOs is only a statement of intent. It does not explain how they will rebalance the influence of their five stakeholders in the way their respective companies are governed. The model advocated by Milton Friedman gives an undue advantage to shareholders (and financial markets) over other stakeholders. Incidentally, it has an impact on the pay structure of the signatory CEOs. Furthermore, in the spirit of the Friedman model, activist investors are often unnecessarily pressuring companies to produce short-term results.

Milton Friedman – (CC) The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice

Research conducted by the International Institute for Management Development (Lausanne) and Temple University (Philadelphia) has highlighted the importance of purpose for companies that achieve strong growth (30% or more per year) in the United States, Europe and Asia: They put purpose at the heart of their strategy. It allows them to reshape their value proposition in the context of a holistic mission and enlarge their scope of activity beyond their traditional markets to open up entire ecosystems.

Consider the example of two companies involved in pet food that are analyzed in this study: Mars Petcare (number one in the world) and Purina (number one in the U.S.). They have the same purpose and almost the same taglines: “A Better World for Pets” and “Better with Pets”.

But, while Purina envisions its purpose as an add-on, Mars Petcare uses it to guide its strategy: It has expanded its portfolio to cover the entire pet health ecosystem, including by making acquisitions, and has given itself a holistic mission by developing a service business.

This transformation required major internal changes, e.g. reorganizations, adaptation of skills and ways of working. Yet, because those changes were guided by a purpose, they were meaningful to employees and, therefore, far less painful to implement.